Jul 13, 2009 0

Leverage and Credit

In an earlier post titled – What is Credit?, a common sense definition of credit was offered:

“There is a strange idea abroad, held by all monetary cranks, that credit is something a banker gives to a man. Credit, on the other hand,is something a man already has. He has it, perhaps, because he already has marketable assets of a greater cash value than the loan for which he is asking. Or he has it because his character and past record have earned it. He brings it into the bank with him. That is why the banker makes him the loan. The banker is not giving him something for nothing. He feels assured of repayment. He is merely exchanging a more liquid form of asset or credit for a less liquid form.”

Of course, this is not what the term means if you were to look it up – you would find a transactional meaning of credit. What I mean is that, credit in practice is the money made available to you by a lender in return for deferred repayment with interest on a fixed schedule. This is the transaction character of the agreement. But embedded in this transaction is an evaluation of the debtor by the creditor as well as the creditor by the debtor.

Now, Credit has a cousin which is Leverage. Now, leverage is an artifact of physics i.e. from Lever. Archimedes said, "Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth." With a lever, the same effort multiplies the result which is to say that one is exploiting this principle of physics. Fast forward to the present time, we use the notion of leverage similarly in human interactions or transactions. To lever up in this context means to be able to obtain credit to multiply the result of one’s (or a firm’s) efforts. But for a moment, go back to the physical world: you borrow a lever, use the lever and return the lever a little longer in length. Doesn’t happen in the real physical world this way but I suppose that would be a way of making a parallel. In fact, you probably paid some money to the owner of the lever which is about equivalent to adding on to the lever’s length.

Now, housing is an accessible form of leverage for the common man. Say, a new homeowner puts down 0%, 10% or even 20% of the value of the home down – that’s what they’re doing, using leverage. In other words, using 20% of their money to control 100% of the house and whatever increase in the value of the home for as long as they make their mortgage payments. But leverage is neutral with respect to the direction of the change in value of the home. If the value of the home was $100,000 and it increased by 10% in one year, then the homeowner who put down 20% of the value of the house or $20,000 increased his worth by $10,000 (not accounting for the interest payments he would have paid out over that period). That’s a 50% increase. But suppose the value of the home decreased by 10%, then, it’s a $10,000 loss which is a 50% decrease in the amount of money the homeowner had to begin with.

Leverage is great in boom times because it multiplies the positives handsomely but in bust times, it magnifies the losses as well especially if you’re unable to ride it out. Now, what possible bearing does all this have on the field of supply chain management for crying out loud.

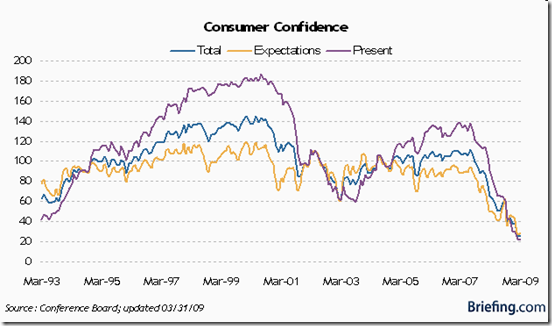

It does but only as far as how consumption or demand was being paid for – whose been underwriting our checks for our fancy gizmos. If during the last decade, demand was being paid for out of income, then this trouble would have some impact (not a devastating one for what it’s worth) on the various supply chains of the world. But if the demand was being paid by milking the fruits of leverage (either directly by taking equity out of the home or indirectly by running up debt via credit cards) during the boom time, then the impact on the various supply chains of the world will be dramatic.

So, the appropriate question is for us in the supply chain world is: What is demand going to look like when leverage is contracting or disappearing? Or in other words, what is demand going to look like when there are no assets left to lever against? What happens when the creditworthy character of the populace upon whom everything depends is in question?

Then add this to the mix, Supply Chain Management is a middle-man activity for the most part. When, this space burst onto the scene, we cut out ten middlemen and inserted three of our own along with a whole host of technological and automated marvels. Being asked to do more with less – a good problem to have but less to do on the whole is a bad problem any which way one cuts it.

But all is not bad – we have on our side the relentless succor of economic experts to help us out of this mess, this predicament. whatever you want to call it. Perhaps, (and I’m stretching to hope here) against every expectation, by the time the fourth stimulus bill would have been passed, things would return to as it where circa 1990. Maybe. By the time the fourth stimulus bill is passed, the populace would be very akin to treating a trillion as nothing more than a billion and congress would have no problem dealing stimulus bills in trillions aka the stimulus bill to cure all earlier stimulii.

My next post should be titled: If economists were running a manufacturing floor? Or something to that effect. My aim is simple, I want to fire the operations manager of my floundering firm and install an economics expert to tell me how to run the place.