Jun 15, 2007 0

Jun 13, 2007 1

Surviving the China Rip Tide – Recommendations??

In the last post – Surviving the China Rip Tide – How to profit from the Supply Chain Bottleneck, I reviewed a report (BCG Report : Surviving the China Rip Tide – How to profit from the Supply Chain Bottleneck) by BCG about certain problems that are cropping up in the China centric supply chain.

In this post, I want to get into the recommendations aspect of that report – What to do about this? The authors of the report advise on how to change this problem into an opportunity. So what kind of opportunities are available? And more importantly, for whom?

First, let me succinctly summarize the current situation:

- Long lead-time supply chains originating from china based sourcing.

- Port congestion at the point of import i.e. US ports

As the authors contend, this is a problem because the lead-times for sourcing from China through congested port infrastructure either on the West coast or East coast of the US are going up. The authors note that,

A leading discount retailer is building distribution centers near the ports of Savannah, GA and Houston, TX in anticipation of the need to redirect its containers from congested west-coast ports.

I agree because in my past role I have executed a number of studies for supply chain network modeling that identified secondary ports and locating distribution centers in relation to these secondary ports that made sense from a distribution point of view. Their recommendations for companies that have yet to go the global sourcing route are as follows:

Reduce minimum production order quantities and reduce cycle times as quickly and as much as possible

In other words, stop batching already and compete on the basis of speed. Thus, produce to demand or transition to a pull model.

Refrain from sourcing or manufacturing in China until management fully understands the dynamics of supply chains.

Or don’t listen to accountants. ![]() Get a handle on total supply chain costs rather than unit costs.

Get a handle on total supply chain costs rather than unit costs.

Create an integrated or semi-integrated information flow within the company’s existing supply chain

Cutting out layers of intermediaries and associated inventories and trying to get as close to the customer as possible is one way to factor not only speed into the producer-customer relationship but also responsiveness. And an information system is an invaluable medium. The question as always is how a firm uses its IT resources over acquiring it.

Jun 1, 2007 0

Surviving the China Rip Tide – How to profit from the Supply Chain Bottleneck

The only hope for these companies is that all their competitors will make the same mistake.

So assert George Stalk Jr. and Kevin Waddell of the Boston Consulting Group in their report titled Surviving the China Rip Tide – How to profit from the Supply Chain Bottleneck. Alright, I’m laughing a little now. Why? Because I said the same thing nearly a year in a general sense of what is going to happen within the supply chain with the onset of globalization/offshoring/outsourcing. (See here: The intimate supply chain – Part 1) This observation was in the context of those who claimed that it was possible to have global lean supply chains and such.

If I may be so bold as to suggest that SCM 1.0 will have been a failure if the kind of scenarios and phenomena that the above authors suggest come to pass. Why? My reasoning is thus: If the push to a global supply chain was done irrespective or without taking into account the total supply chain cost (instead being driven by some instinctual feeling of lower unit costs and the like), then SCM 1.0 will have been a failure. Over the last year, It was quite commonplace to see supply chain professionals envisioning lower inventories in a global supply chain. That is plainly wrong. In a global supply chain, inventories will rise as firms not only have to work with lower quality products (in the initial stages) but account for the longer lead times of logistics. So what happens when all that globally sourced inventory has to pass through a chokepoint before they get stateside i.e. when the ports are the bottleneck?

Now, back to the report:

But competitors that do not source from China – or that do focus on supply chain speed – will be competing with a different set of economics. The first company to see and correct the strategic error of sourcing from China without an appropriate investment in supply chain dynamics to minimize costs will seal the fate of its competitors.

First things first, I must communicate my position as clearly as possible. I am agnostic as to whether offshoring/outsourcing is better than insourcing/inshoring. I am as pleased at the immense economic opportunity presented to millions overseas as dismayed by the havoc that outsourcing creates stateside. However, the choices before firms are stark as well and this is where Taichi Ohno’s remarks are rather appealing. Do take the time to read this rather insightful piece, Panta Rei: Gemba Keiei, Chapter 6: The blind spot in cost calculation Here is my take on the same – The blind spot in cost calculation… Whatever the competing economics that firms that source globally or source locally have to face, the above described notion of cost must be engaged i.e.

Cost do not exist to be calculated. Costs exist to be reduced.

If you are a sourcing or supply chain professional, there are two chapters in this report you would need to pay special attention to because they present good insights. One isd the The Hidden Costs in Supply Chains and the other is The Dangers of Lengthening Supply Chains. In the analysis presented in The Hidden Costs in Supply Chains, the authors elaborate on the notion of direct, indirect and hidden costs. They expand direct and indirect costs as:

Direct and indirect costs include shipping, nesting and de-nesting of containers at both ends of the ocean pipeline, inventory storage, handling, procurement, insurance and overall financing.

According to the authors,

These costs can eventually add up to as much as 4 to 8 percent of retail shelf costs.

However, they contend that the largest costs i.e. hidden costs

they come from the gross margins that are lost when the product isn’t there for the consumer to purchase. The gross margins of the products in Exhibit 4 can range from 40 to 60 percent of the shelf price.

Moreover they add,

the cost of excess inventory write-downs from having an oversupply of products that consumers don’t want can amount to 10 to 20 percent of sales.

There is one more component of hidden costs that the authors have not taken into account – it’s a behavioral component which is again difficult to quantify but has been uniformly (except perhaps for Lean based manufacturing) the bane of traditional manufacturing and/or sourcing. And yes, this is from Jay Forrester’s book on the topic of industrial dynamics – Industrial Dynamics. Distill it this way, the longer it takes for stuff to move through a supply chain, the longer it is subject to Murphy’s law. Or what has increased in a longer supply chain (such as one from a global sourcing location in China/India) is uncertainty. And uncertainty (be it positive or negative) means dollars in costs. For example, if your shipment arrived 2 days earlier than it was supposed to – what some might desire to call positive uncertainty, perhaps you have to now acquire a truck to dray the shipment at spot rate instead of a contracted rate. Or you have to pay storage costs at the port if truck capacity is strained. Better yet, if you brought the shipment to the production firm or retail outlet, you have to deal with the products within your system earlier than expected. Uncertainty propogates through a system like waves that have been initiated in a narrow channel and as it bounces of the system walls, it creates even more uncertainty. That means dollars spent every which way trying to manage the uncertainty in the system. If I were to succintly describe the overarching purpose of middle management, it is to reduce uncertainty in the system. I hope a clearer picture about the types of costs in the system has been acquired.

Now about the natural behavioral component of management that the authors have missed out. In a system that is susceptible to uncertainty, be it of lead times (compounded in a long supply chain) or bottlenecks, you have to compensate for the uncertainty, at the minimum, using inventory. In the current scenario, a firm sourcing from China requires inventory to cover the logistical lead times but when you throw uncertainty into the mix, inventories have to increase. Thus, if you have a bottleneck in your supply chain right now with the inventory required today, as managers react to the uncertainty of going through a congested port or transportation infrastructure, required inventory (and thus shipped volumes) rises which in turn causes more congestion – do you see the problem? This problem will ripple in both directions i.e. for the producers as well as suppliers. In the analysis presented in The Dangers of Lengthening Supply Chains, the authors simulate the scenario of a supply chain originating closer to the US (Central Europe) with a scenario of a supply chain originating far away (China). They test out the effects of information flow and tightly coupled manufacturing to demand scenarios.

The key takeaway for me from this report is that the rose colored glasses that has so far accompanied the rush to China or other overseas locations is letting some light through. In short, the free lunch is about to get pricey. In the next post, I hope to get into what firms can do other than hoping that their competitors have made or will make the same mistakes of jumping with both feet.

Tags: Surviving the China Rip Tide – How to profit from the Supply Chain Bottleneck, Boston Consulting Group, George Stalk Jr., System Dynamics, Kevin Waddell, Jay Forrester, Offshoring vs. Inshoring, Outsourcing – the rose colored glasses, Uncertainty

Apr 24, 2007 0

Supply Chain Network Optimization and Competitive Advantage – Part 2

In Supply Chain Network Optimization and Competitive Advantage – Part 1, I began exploring the notion articulated by SC Digest’s editor Dan Gilmore in a recent post about Supply Chain Network Optimization and Competitive Advantage. In the article Mr. Gilmore goes on to describe how a few companies are adopting this particular aspect of Supply Chain Management in their processes so much so that it is seen as a source of competitive advantage.

In Part 1, I explored whether the use of such network modeling and optimization tools constitute a true competitive advantage and finding in the negative, I hope to explore what it might really be called. But before getting there, I need to revisit the notion of competitive advantage again (and not for the last time). As explored in the previous post, the essential components of a competitive advantage are:

1. A member of {Demand Competitive Advantage (Customer Captivity), Patented/Superior Technology, Economies of Scale}

2. Provides a barrier to entry

3. Realizes a net positive return on some Sales-Cost metric

As Greenwald and Kahn note in their article – All strategy is local, there is an essential difference between Strategy and Efficiency. Strategy is (Oh well! – change that to “should be”) cognizant of (if not focused on) the other players in the arena – thus outward looking. A strategy that doesn’t assert (based on the probable reactions of competitors) or react (based on the actions of competitors) can be effective if only luckily so. However, while the formulation of a strategy is outward focused, executing a strategy is limited by what is available internally. Efficiency on the other hand is very much focused on internal structure, processes and in an advanced case collaboration and partnership with key suppliers and enablers. Efficiency might have a focus on the efficiency benchmark from other players in the arena (or in the case of benchmarking – players that are quite unrelated in the competitive space) but again it is not related to the topic of competition per se. As the authors note,

A company’s best and most innovative users of information technology, business models, financial engineering and almost everything else that applies to operations suffer from the same availability to rivals. What a firm can do, its competitors can eventually do as well. IT effectiveness, HR policies, financial strategies, and so on are essentially aspects of what it means to operate efficiently.

So where does the above discussion leave the supply chain planning and network optimization function?

Apr 15, 2007 1

Supply Chain Network Optimization and Competitive Advantage – Part 1

SC Digest’s editor Dan Gilmore has a recent post about Supply Chain Network Optimization and Competitive Advantage and how a few companies are adopting this particular aspect of Supply Chain Management in their processes so much so that it maybe a source of competitive advantage.

While I am quite convinced about the need for strategic planning for supply chains at the highest echelons of management using the very kinds of tools that Dan Gilmore is talking about, I am hesitant, if not quite in the opposite camp, when the use of such tools is deemed to confer, even offer, a competitive advantage. The opportunity of deriving a competitive advantage this way is minimal at best. What is competitive advantage and what is not is the subject of this part of the series. In following parts, I hope to identify what supply chain planning and optimization really is.

In order to explain myself, I need to first elucidate the very notion of competitive advantage and strategy (or strategizing). I refer you to the excellent article on strategy: All strategy is local by Bruce Greenwald and Judd Kahn. The byline of their article states that:

True competitive advantages are harder to find and maintain than people realize. The odds are best in tightly drawn markets, not big sprawling ones.

The aim of true strategy in their opinion is,

to master a market environment by understanding and anticipating the actions of other economic agents, especially competitors. But this is possible only if they are limited in number. A firm that has privileged access to customers or suppliers or that benefits from some other competitive advantage will have few of these agents to contend with. Potential competitors without an advantage, if they have their wits about them, will choose to stay away. Thus, competitive advantages are actually barriers to entry {emphasis is mine}. Indeed, the two are, for all intents and purposes, indistinguishable.

Greenwald and Kahn contend that true competitive advantages, whatever their source, are really barriers to entry – in the sense that gaining such a competitive advantage presents a significant threshold to be scaled. The conclusion is an acceptable one and as you can imagine begins to chip away at the notion that the use of supply chain strategic planning tools in some way offer a competitive advantage. I think there is a case to be made about sources of competitive advantage with regards to all aspects of supply chain management within a firm. I do not see that the output of supply chain strategic planning (which is a streamlined and robust supply chain network) offers any real competitive advantage. To belabor the point, any competitive advantage that can be easily replicated is not an advantage, it is the entry price for remaining in the competitive arena.

Dec 15, 2006 1

Different Priorities – Investment Prioritization for Manufacturing Software

IndustryWeek reports on investment prioritization for manufacturing operations software and how it varies across different industry segments in a recent article titled – Different Priorities.

According to the report,

# In chemicals, 28% of the manufacturing budget will be applied to advanced process control and simulation.

# In aerospace and defense, 50% of the manufacturing budget will be applied to quality management systems.

# In pharmaceuticals, almost 45% of the manufacturing spending will be applied to quality management (if LIMS is included), 20% on recipe/formula/specification management and 20% on enterprise manufacturing intelligence (EMI).

# Automotive, high-tech and industrial products are prioritizing MES (29%, 32% and 35% respectively).

# The consumer products industry is spending the largest share of any industry’s manufacturing budget on EAM, at 16%.

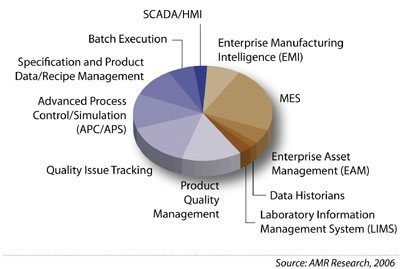

The other interesting tidbit is captured in this pie graph:

As the report highlights, pharmaceuticals, aerospace and defense are trending towards quality management systems which is a sizeable market area to address if you were a provider of software systems. So the obvious question then is what are the quality management systems out there? Further, is quality management a COTS (Commercial Off-the Shelf Software) type of solution or something more substantial (and messy as well).

The second category of interest is MES (Manufacturing Execution Systems) which garners significant interest across the segments of automotive, high-tech and industrial products. The surprising (or perhaps, not so surprising) thing about MES is highlighted in this article here.

“In 2001 the vast majority of the Fortune 1000 manufacturers AMR Research surveyed were in the throes of massive ERP rollouts,” says senior research analyst Alison Smith. “As these draw to a close, manufacturers are realizing that their ability to effectively measure and manage the performance of their manufacturing assets hasn’t proportionately improved.”

What happened here – manufacturers are realizing that their ability to effectively measure and manage the performance of their manufacturing assets hasn’t proportionately improved? Is it simply that knowing what is happening doesn’t mean that you know what to do about it? Or is it just an informational glut of too many metrics that have not been pulled together into a coherent manufacturing execution philosophy?

The last category of interest is the advanced process control and simulation software as applicable to chemicals industrial segment.

One thing stands out in all these major categories of investment interest i.e. finding the silver bullet for business execution. These systems are central to the functioning of the business i.e. they are core systems. Even in the quality management systems of interest in the first category, I would argue that it is a core function of the firm. From this, there is an indication that the promises of ERP or similar systems have not actually panned out in actuality. That’s good to know because the need is still there.

Tags: Manufacturing Software, Investment Priority, AMR Research, IndustryWeek

Dec 2, 2006 1

Healthy paranoia drives investment in supply management – Part 2

In Part 1 of Healthy paranoia drives investment in supply management, I explored issues in supply management as illustrated in Global Logistics & Supply Chain Strategies Magazine (online version) – an article in their recent edition is on Investment in Supply Management. The article was authored by Jean V. Murphy.

In the previous part, I explored what firms view as supply management and what solution providers view as Supplier Relationship Management (SRM). In this part, I will explore how firms think about supplier management and supplier networks and the steps that firms could take to structure their relationships vis a vis their suppliers as outlined in the article.

Jean outlines the steps that comprise supplier management as follows:

Core Suppliers

Jean notes that the first step is,

identifying key suppliers that are core to a company’s operations and that warrants establishment of joint processes and communications.

And,

So the first step in formalizing a supplier management program is having visibility to your suppliers and how much of your enterprise they supply.

What I find surprising is that when it comes to supplier management, firms are sometimes clueless about where and how they spend their dollars. This point would not have arisen if firms had a firm idea of the power of their suppliers (harkening to the Five forces model from Michael Porter).